The advantage of living under the First Amendment is that it allows you to speak, write and worship as you please. But there’s also a problem with living under the First Amendment: Sooner or later, it’s going to protect someone you detest.

Some conservative Christian towns don’t want mosques. Some liberals wouldn’t mind blocking the Westboro Baptist Church’s anti-gay demonstrations. Some whites regard Black Lives Matter protesters as dangerous extremists. Anti-Trump Americans see MAGA crowds the same way.

The price of being able to advocate your beliefs and practice your religion, or your irreligion, is that people with starkly incompatible beliefs and gods are able to do the same.

It’s a tradeoff not everyone accepts.

Among them are leftists such as Georgetown law professor K-Sue Park. She has criticized the American Civil Liberties Union for defending the rights of right-wingers, arguing that doing so “perpetuates a misguided theory that all radical views are equal.”

The awkward effects of the First Amendment are visible in the Minnesota town of Murdock, where a white supremacist group that presents itself as a religious sect bought an old church to serve as its base. Some residents regard the intrusion as harmful to their welfare and the values of the community, according to a story in The Washington Post, and urged the city council to deny a permit to the Asatru Folk Assembly. But the council, fearing a costly lawsuit that it would lose, voted to grant it.

Christian Duruji, who is Black, told the Post, “I fail to see how a group that would reject me on sight and view my daughter as an aberration not to be celebrated” would be good for Murdock. Northwestern sociologist Laura Beth Nielsen lamented, “In the big picture, the First Amendment is reinforcing who already has power.”

But freedom of expression is good for every town. And it’s hard to make the case that much power lies in a fringe group claiming to practice an ancient Nordic faith that few people have ever heard of.

White people often benefit from the First Amendment because there are lots of white people in America and some have opinions that would not come out of Fred Rogers’ mouth.

But the same protection extends to other groups that lack political or economic might.

Historically, says University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey Stone, “laws restricting speech in our nation have been directed primarily against those who opposed a war, those who advocated Socialism or Communism, those who advocated for civil rights, those who engaged in sexually-oriented expression and those who advocated for the rights to contraception and abortion.” Only a broad and neutral application of the First Amendment has given them relief.

The FBI is the epitome of government power. But last week, the Supreme Court dealt it a loss by allowing a lawsuit by three Muslim men who were placed on the no-fly list for refusing to serve as informants. The court said that federal law allows such damages “for clearly established violations of the First Amendment.”

Without the First Amendment, people whose religious views are in the minority would be at perpetual risk. If one town could bar the AFA, another could reject a mosque, a synagogue or an atheist group.

The First Amendment has spurred the Pentagon to allow Wiccan symbols on the graves of soldiers in military cemeteries. It has obliged towns to allow mosques in the teeth of anti-Muslim sentiment.

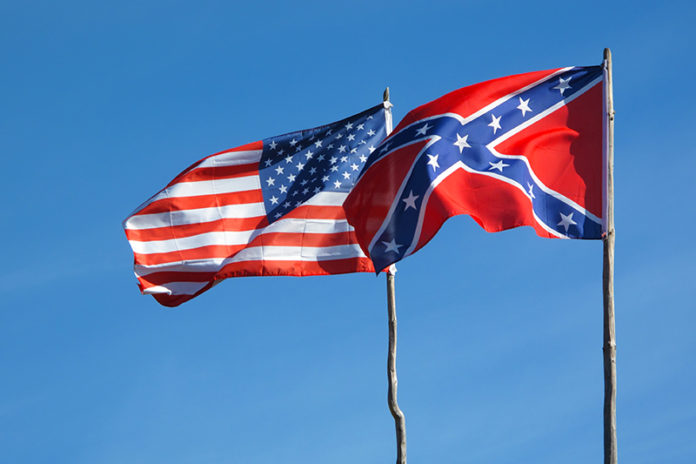

White supremacists have lost fights over Confederate monuments because opponents have had the right to mobilize against them. If a band of protesters had lacked the freedom to rally against the Christopher Columbus statues in Chicago, those sculptures might still be in place.

In 2000, Congress passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act to buttress these protections. This year, the Department of Justice reported that “RLUIPA claims in institutional settings are most often raised by people who practice minority faiths,” noting that “the majority of the cases the Department has pursued involving religions other than Christianity.”

Jews and Muslims, it noted, make up 3% of the U.S. population, but investigations involving them account for 33% of its cases. Buddhists and Hindus are also overrepresented.

It may be tempting to dream of narrowing the First Amendment so that we could more easily combat hateful groups. But if its protections were ever weakened, it’s not oppressed minorities who would reap the benefit. It’s the oppressors.