Let’s talk about the constitutional significance of bushes at the foot of the 40-foot-high, 16-ton concrete Latin cross that sits in the middle of a busy highway intersection at the entrance to Bladensburg, Maryland. Or maybe let’s not.

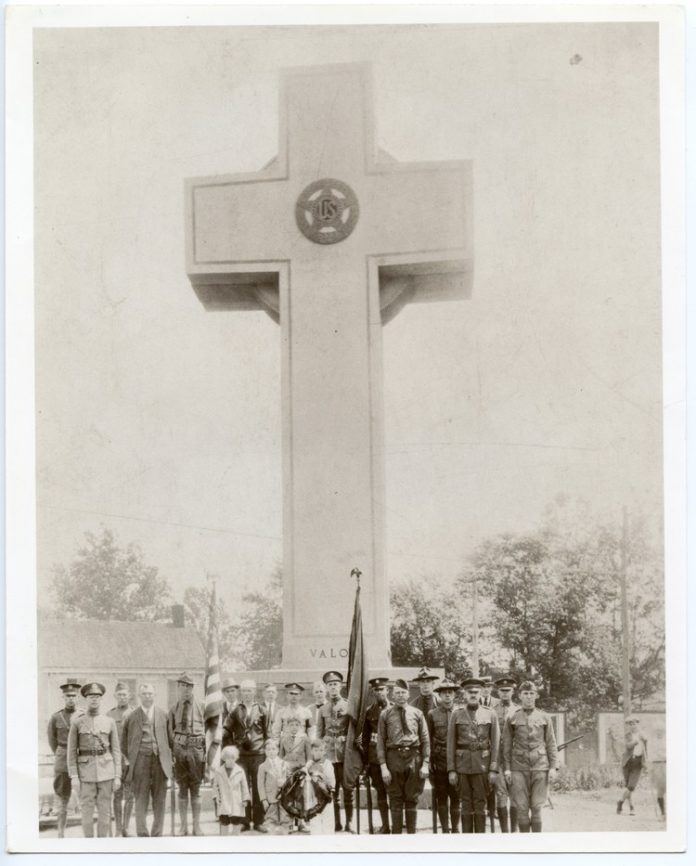

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court is considering whether that monument, which was erected nearly a century ago in honor of 49 local men who died in World War I, amounts to an “establishment of religion” prohibited by the First Amendment. The case shows how confused and confusing the court’s jurisprudence in this area has become.

Under the test the court described in the 1971 case Lemon v. Kurtzman, a government-sponsored display violates the Establishment Clause if it lacks a secular purpose, if its “principal or primary effect” is to advance or inhibit religion or if it fosters “an excessive government entanglement with religion.” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, which in 2017 ruled that the Bladensburg cross is unconstitutional, thought the bushes were relevant to this analysis because, until recently, they obscured the plaque inscribed with the names of those 49 dead soldiers along with a quote from Woodrow Wilson justifying U.S. involvement in one of history’s most senseless and devastating wars.

Because those references to World War I for a long time were not visible to passers-by, the appeals court reasoned, the monument’s secular aspect was overshadowed by its religious significance. Recognizing the potential legal importance of the bushes, the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, which has owned and maintained the cross since 1960, cleared the bushes away in 2014 after three local residents and the American Humanist Association challenged the monument in federal court.

The case is not all about the bushes, of course. It is also about the memorial’s size, its modeling after “the Cross of Calvary, as described in the Bible,” its conspicuous location, its distance from other war memorials in the area and the exclusively Christian nature of the prayers periodically performed at the site.

Based on factors like these, the 4th Circuit concluded that “a reasonable observer would fairly understand the Cross to have the primary effect of endorsing religion.” And because the monument is located on public property and maintained with public money, it represents an “excessive entanglement” of government with religion.

Or maybe not. Chief Judge Roger Gregory, who dissented, thought the majority’s “reasonable observer” was unreasonable and deemed the Bladensburg cross consistent with Supreme Court rulings blessing “displays with religious content” that also have “a legitimate secular use.”

Who is right? Who knows! The Supreme Court’s decisions in cases such as this are a muddle.

The court has said a nativity scene in a city square is constitutional but a nativity scene in a courthouse is not. It has ruled that the Ten Commandments have no place in public schools or courthouses but are OK on a 6-foot monolith near a state capitol, provided it is surrounded by other monuments and the text is “nonsectarian,” which seems impossible.

The court’s puzzling reasoning in these cases invites arguments that are either disingenuous or oblivious. The commission in charge of the Bladensburg cross, for instance, claims a gargantuan rendering of Christianity’s central icon is a “benign” symbol of “military valor and sacrifice” that Americans can embrace “irrespective of their religion.”

For non-Christians, a giant government-sponsored cross does not inspire warm and fuzzy feelings about shared values. It looks instead like the majority is promoting its religious beliefs at taxpayers’ expense. The question is whether the Constitution forbids that sort of thing.

In a brief urging the Supreme Court to ditch the highly subjective “Lemon test,” the Cato Institute argues that “the Establishment Clause was designed to prevent religious persecution, not to eradicate religious symbols from public life.” In other words, the clause prohibits the establishment of an official religion but not much else. The more Establishment Clause cases you read, the more appealing that approach looks.